At a recent meeting of the Crosslands Energy Committee, there was a brief debate about the merits of the reusable green plastic take-out containers vs. the white single-use biodegradable ones made of heavy paper. The plastic ones are much more expensive, and once they become unusable, they end up in the landfill, where they will take a great many years to decompose. The paper ones get used only once, but they will readily decompose in the landfill. So which is really better?

Questions we don’t know how to answer. The two types of containers are hard to compare. When the paper containers decompose, do they release C02? How much? Is that OK because it’s just CO2 that was previously captured from the atmosphere by the tree from which the paper was made? Or if the paper containers are buried and not exposed to the air, do they release methane when they decompose?

Different questions can be asked about the plastic containers. They are made of polypropylene (#5 plastic) which is recyclable, at least in theory. Once their working life is over, do they actually get recycled? If they go to the dump, do they eventually break down and release CO2? How soon, and how much CO2?

These are questions I don’t have answers to.

Cost and durability. On the other hand, I do have some answers about the relative cost and durability of the containers. The cost part is pretty easy. The container I brought home my supper in is a polypropylene container from the “Eco Take-out Series” sold by G.E.T. of Houston, TX. These containers are easily found on the web. When bought in bulk, they cost $4-$5 each. The paper ones cost only about 10% of that—around $0.50.

So we can get 10 of the paper ones for the cost of each plastic one. The purchase price isn’t the entire cost to Kendal, of course. The plastic ones have to be collected and washed after each use. So let’s say that their actual cost over many uses is $20 each.

Given that cost estimate, the plastic ones would need to be durable enough to last at least 40 uses to match the low cost of the paper containers. Do they?

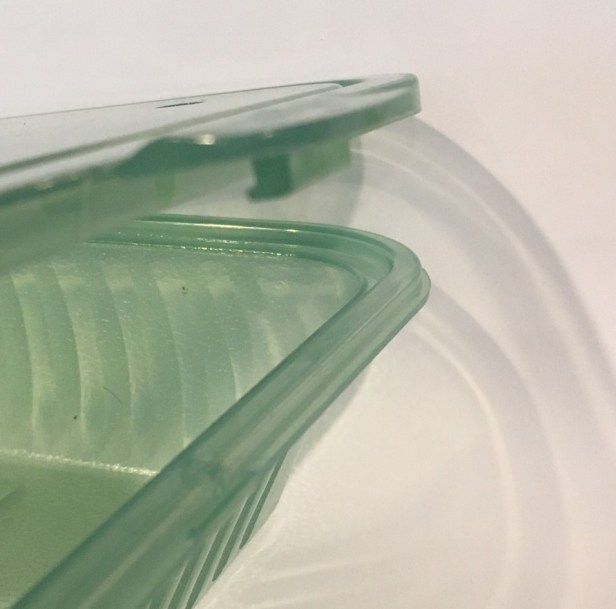

Among the group discussing this topic, there was agreement that the latch mechanism of the plastic containers was the most likely point of failure. Several of us had seen containers with the latch missing or at least partially broken. So the question became: how many times can a plastic container be latched and unlatched before it breaks and becomes unusable?

An experiment. I decided to put one of the plastic containers to the test. I took the new-looking one that I had brought my food home in and washed it. Then, I started latching and unlatching it, looking for signs of breakage. I did 100 latch/unlatch sequences, with no sign of breakage. So I did another 100 sequences, and finally a third set, for a total of 300 sets of latch/unlatch. After that abuse, I still could find no sign of wear and tear on either the upper or lower part of the latch mechanism. I’m convinced that the container was good for far more than 300 uses.

This experiment convinced me that the plastic containers are a far better financial investment than the paper ones. In terms of the environment, I admit that plastic containers are a bad idea in general. And the plastic will become more brittle with age. But in this case, I believe the plastic container is going to survive a year of use, maybe two, before it goes in the trash. That means it will take the place of hundreds of single-use paper containers. I accept that as a reasonable tradeoff, and so I favor the plastic containers.

But instead of focusing on the possible limitations of the full-size plastic take-out containers, perhaps we should take a closer look at the smaller single-use plastic containers used for sandwiches, salads, and deserts. These are made of hard-to-recycle #6 plastic (polystyrene). Why don’t we replace them with reusable plastic ones (like the green one I tested, only smaller)? Kendal at Ithaca seems to already have made the switch. On a visit there, I saw the smaller green containers in use. I think the case for making that switch here will be overwhelming, on both financial and environmental grounds.

Re: Cost, durability, environmental and safety issues related to plastic containers.

A serious analysis of the use of plastic containers rapidly becomes complex. Consider the “40 uses” example. The monetary and environmental costs associated with cleaning staff salary, cleaning equipment maintenance, water usage and heating, cleaning chemicals, and resident superficial rinsing before return, must be taken into account. And, what percentage are never returned?

Many containers I’ve received are severely stained from previous meals. This raises hygiene issues. Are the stains do to poor cleaning or is the plastic reacting chemically with certain foods. And, if a chemical reaction is taking place are harmful chemicals being released into the food being served?

LikeLike

Interesting info. Several comments:

1. there are several versions of the green containers so wonder if other latches would stand up as well?

2. Yes, we should definitely use the small green ones instead of the #6s.

3. To be biodegradable and useful in compost, those white ones must be broken down/cut into small pieces. I question whether most people will take the time to do that?

LikeLike

What about taking our own containers for take-out meals? I’ve been using my Tupperware containers for years, and they last!

LikeLike

Although the white takeout containers appear to be paper or cardboard, they are not. They are made of sugarcane bagasse (fibrous pulp left after squeezing juice from sugarcane stalks), which is presumably biodegradable and compostable (in an aerobic setting). And, sugarcane can be grown much faster than trees, making it more sustainable than paper or cardboard. However, the containers are not recyclable and therefore must be thrown into the trash, since KCC does not participate in an aerobic commercial composting program. The white containers will go to the landfill with the other trash, where they most likely will take a long time to decompose. This makes the reusable green takeout containers, as stated in the blog, a MUCH better choice for the environment.

LikeLike

I entirely agree–green for me! Another strike against the white ones: if you don’t eat your meal immediately, you’ll find that they get soggy on the bottom, maybe enough to dampen whatever they’re sitting on. (Nice tablecloth? mahogany table?)

LikeLike

Interesting that the “paper “ containers are biodegradable if oxygen is present. That means we could cut them up and put them into our neighborhood composters, right? This would be another good reason to encourage more neighborhood composting. We now have four composting operations spread through Kendal. Maintenance is a chore, but if there are three or so participants, it can work well. The paper containers would help the balance of wet and dry materials in composting ingredients— a plus. So far as bringing our own food containers, no one objects to this at Kendal, though we’re told there are some kind of health restrictions . I would like to know what and where. Seems to me the negatives due to germs (or whatever) pale in comparison with the negatives due to polluting our planet.

LikeLike

The comparison should include staff time/cost to collect, rinse, wash and restack …. plastic containers.

LikeLike