Kendal-Crosslands (KCC) has always used electric heating in the cottages and apartments. Right from the start, in 1972, the only place natural gas was used for heating was in the Kendal Center. At the beginning, everything was baseboard heating, but KCC has gradually been transitioning to heat pumps. When Kendal’s duplex units were built in 2012, they used geothermal wells and ground-source heat pumps. In other units, air-source heat pumps have been gradually replacing baseboard electrical heating and stand-alone air conditioners. A major reason for the changes has been saving on the cost of electricity.

Does your heat pump save electricity? Could it save more? In principle, a heat pump can save two thirds of the electricity for heating that a baseboard unit requires for the same amount of heat. Baseboard heaters use resistance heating (hot wires, the same process as your toaster) to heat the air, but a heat pump moves heat from the outside air indoors. (Surprisingly, there is always some heat available from the outside air. A good, efficient heat pump can heat a building even in very cold weather. But it does have to work harder in colder temperatures.) Moving heat uses far less electricity than heating up a wire.

But still, we are not getting a lot of the expected savings on our electricity. That’s because of the way our thermostats work.

The behavior of your heat pump is controlled by your thermostat settings. Crosslands resident Ben James began exploring the data captured by his Bryant thermostat (and those of his friends and neighbors) and discovered a problem. Our heat pump units contain both a heat pump and a resistance heating unit. The resistance heating is there to supplement the heat pump to accelerate warming when a significant increase in temperature is needed. (What’s “significant”? Bryant doesn’t reveal that, but Ben’s experience suggests it may mean “turning your thermostat up more than two degrees”) The heat pump itself could generate the requested temperature increase, but it would take longer.

Unfortunately, a lot of us turn down our thermostats at night or when we’re away for multiple days, and that can cause the resistance heating to kick in when we turn them back up. The result is a burst of electricity use. The amount of electricity (and the cost) is about three times what it would have been if the heat pump had gradually increased the temperature by itself.

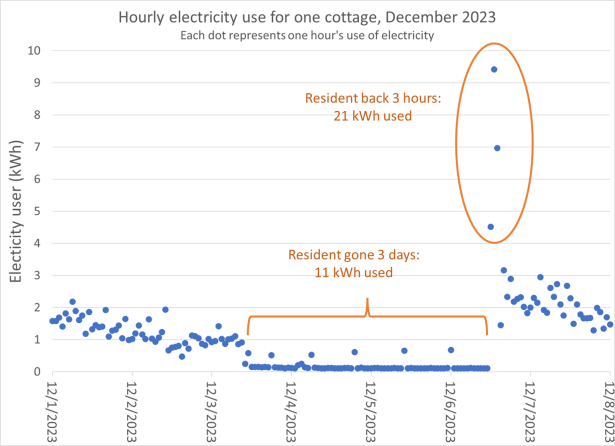

Resistance heating can cause a huge spike. The following graph of electricity use from a cottage outfitted with electrical monitoring shows the spike that results. The temperature in the cottage was turned down while the resident was away, then turned back up when they returned.

In some cases, Ben James’ data shows, residents are using more electricity during these short resistance-heating spikes than they use for heat-pump heating the entire rest of the year.

For some time, Ben has been requesting a meeting with a representative of Bryant (the brand of heat pump systems we use). Roy Manno set up such a meeting, on Zoom, and it occurred last Thursday (1/16/25). The representative was Patrick Moran, who does tech support on the Bryant systems. Moran works for Pierce Phelps, the regional distributor for Carrier/Bryant air conditioning and heating equipment.

Can a “temperature lockout” solve our problem? In the Zoom call, Moran’s basic message was that there is only one feature in the thermostat software that can help address this problem. It is called a “temperature lockout” and it depends on the outside temperature. If the temperature outdoors is above the lockout temperature, the resistance heating will not be used in most cases. There is an exception, however: if the thermostat senses a temperature in the residence that is at least 8 degrees colder than the current setting, the thermostat logic decides it is an emergency, the lockout (if if one has been set) is overridden, and the resistance heating kicks in.

So, for example, if your thermostat has its lockout temperature set at 50 degrees and the outside temperature is 51 degrees, the resistance heating will normally not be used, regardless of the thermostat setting. Unless you exceed the 8-degree range for lockout override, the resistance heating will be “locked out” and the heat pump alone will raise your temperature to the level you have set.

Ben James has had his lockout temperature set at 35 degrees for more than a year and has not experienced any discomfort. His heat pump has always raised the temperature to whatever the thermostat was set at, quickly enough to suit him. As a result, he has used very little resistance heating.

In principle, then, many of us could live with a moderate lockout temperature (40 degrees, for example) and rarely use our resistance heating. We might not even miss it.

In practice, however, it isn’t very easy to change your lockout temperature. It requires diving deep into the maintenance features of your thermostat. And, to make matters worse, the default setting of our thermostats is NO lockout temperature. The outside temperature might be 60 degrees, but if you happen to ask for a 3-degree increase of your indoor temperature, the resistance heating may kick in.

To actually use the lockout feature, you’ll need help from a knowledgeable resident (like Ben) or from the Facilities Department.

How about a constant temperature? One solution that will work for some people is to leave their thermostat set at the same temperature, day and night. Then, the resistance heating will be used rarely, if ever. But if you like it cooler at night, or if you want less heat to be used while you are travelling, that approach won’t solve the problem.

To minimize use of resistance heating without resorting to a constant temperature, Moran recommends that we keep our thermostats within a range of +/- 5 degrees. But then resistance heating will still get used at times.

What might be done in the future? People on the Zoom call had some ideas for how the thermostat software could serve our needs better, if it had the right features. Moran has offered to take our suggestions to one of the “voice of the customer” meetings that Bryant runs periodically to collect complaints and suggestions.

Among the suggestions were these:

- Upgrade all thermostats to a software version that supports temperature lock outs (some versions do not). Send around trained residents, staff, or contractors with memory cards to update the software and set a lockout temperature for those who want it.

- Provide an “Eco” mode (similar to what some cars have) so that residents can easily choose to reduce their use of resistance heat.

- Provide a way to reduce the amount of resistance heat in our heat pumps. The resistance heating coils are far more powerful than the baseboard heat that was originally in our cottages and apartments. Our backup generators were designed to handle that baseboard load. If the power went out during bitter cold weather, our backup generators might not handle the increased load of the resistance coils in our heat pumps.

- Provide a way for the Facilities Department to remotely control our thermostats, so that those who wish to participate in our “Peak Alert” and similar programs could sign up to have it happen automatically.

Moran promised to take our ideas to the next “voice of the customer” meeting, but he cautioned us not to expect changes any time soon. He also noted that we are unlike most Bryant customers, who are happy if their installation just provides the heat they want, when the want it.