We’ll be seeing a significant increase in the cost of our electricity in the coming year, and the increases will probably continue for years to come. PJM, our regional grid operator, is adding a big surcharge to our bill. Data centers are a big part of the reason. That’s the subject of this blog post.

Let me be clear from the start: this is not because of our new contract for wind energy, which won’t affect the PJM surcharge one way or the other. Our new solar panels will help a bit, but there are too few of them to make a significant impact.

The capacity charge. In addition to the cost of generating and distributing the electricity we receive, PJM adds a “capacity charge” to each bill. In some years, it is a small fraction of our bill. In others, it can be up to a third. The capacity charge is paid by all “commercial” users (not single-family homes) in the PJM region, which stretches south to Virginia and west to Chicago.

The concept of the capacity market is that it will encourage enough standby generation capacity to get the PJM region through peak periods without blackouts. PJM uses the revenue from capacity charges, like the ones we pay, for capacity payments to grid-connected generating companies with standby generating capacity. Specifically, the capacity market is designed to pay generating companies to hold enough generating capacity in reserve to cover a demand that is 20% greater than the highest peak that PJM anticipates during the next three years.

The companies are paid whether or not they are ever called upon to turn on the standby capacity. This encourages the companies to build a bit of excess generating capacity, just in case it’s needed.

Users, such as KCC, who are classified as “commercial” accounts, pay for that standby capacity via the capacity charge. The amount we pay depends on how much electricity we use during PJM peak demand. The PJM observes the power that all commercial accounts use during a given year’s five hours of peak electricity use, and it divides up the total capacity charge proportionately. (This is the principle that drives our “Peak Alert” program. We are trying to reduce our use during the 5 peak hours so that we are assessed a smaller capacity charge.)

The data centers. The capacity market has worked reasonably well in the past. But the sudden growth of power-hungry AI (and, to a lesser extent, power-hungry cryptocurrency “mining”) is demanding huge new sources of electricity. The companies that are betting big on AI (notably Google, Meta, Microsoft, and OpenAI) are willing to pay whatever it takes to lock in additional electricity supplies over the next few years.

At the same time, the 13 states served by PJM have become worried about the potential for huge spikes in electric bills due to rising capacity charges. Pennsylvania’s Governor Josh Shapiro, in particular, has been aggressive in trying to contain these charges. He filed a lawsuit against PJM to require a cap on the charges. He was able to obtain a settlement limiting the growth of the charges.

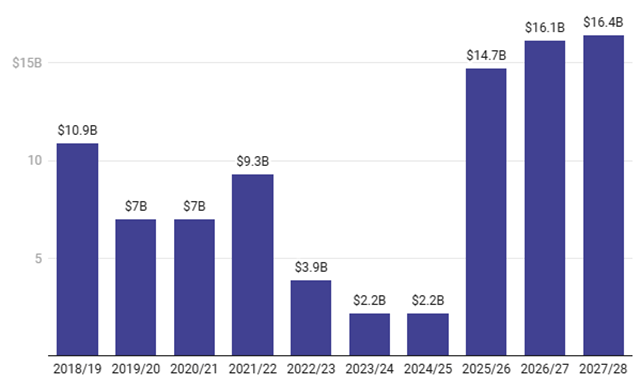

That had the intended effect in terms of the prices PJM is paying for standby power. But it had a perverse consequence too: Power companies now see that they can earn more through contracts with AI companies than by holding reserves for PJM’s capacity market. As a result, despite offering to pay far higher rates than in the past, PJM fell far short of securing the 20% margin over predicted demand that it wanted in the latest auction (covering the 2027/2028 year). PJM may be dangerously short of generating capacity within three years—possibly sooner. And beyond three years, it is likely to get worse.

It’s unclear how this problem will be resolved. But this much is clear: commercial users (that’s us) are being asked to compete for generating resources with the AI companies, and it is driving up our rates dramatically. We will not only be paying more, but—if things stay as they are–PJM may have to cut off our power during really high peaks of electricity demand.

Here in Pennsylvania, there is no chance that generating plants will be built quickly enough to serve both the anticipated needs of the AI companies and the regular users. It’s conceivable that solar-plus-battery systems could manage it, but the rules for connecting that type of generation to the grid are so onerous that it clearly won’t happen fast enough. Unless something changes, we could be headed for an electricity crisis sometime between now and 2030.

No help from Texas wind or solar panels. Our surcharge from PJM is based on the electricity we receive from the grid. Our wind energy deal doesn’t affect that. In principle, our solar panels could affect it, but we’d have to have far more of them. The ones we have now can only generate one or two percent of our electricity, so there won’t be a significant impact on our use of grid electricity.

This means that our Peak Alert program will be more important than ever, for at least the next few years. After that, maybe the combination of more generation on the grid and more solar panels here will lead to a reduction in our capacity charge.

Thinking about this, I am left with a sense of unfairness. Why is it that, when huge corporations want to build data centers to run their AI software, the electricity bills for the rest of us skyrocket? These companies, and the cryptocurrency miners who represent the other major category of data center users, have lots of capital and huge profits. Ordinary people are getting very little of the benefit. Shouldn’t those companies be paying for this? Shouldn’t they be the ones ensuring the electricity supply for the rest of us?