My family has a holiday tradition of making balls woven with six ribbons. My father, Howard Alexander, a mathematician with a strong interest in geometry, discovered how to make these ribbon balls back in the 1930s. They have been a family tradition ever since. As far back as I can remember, we made these balls and colored paper chains to decorate our Christmas tree. All five of us kids learned the technique.

According to family lore, after his engagement to my mother, they went on a long bus trip to Cleveland to meet her parents. During the trip, he fell silent for a time, and she worried he was having second thoughts. It turned out he was mentally working out the process for making these balls.

Dad christened his ball a “dodecaball” because the symmetry is that of a 12-sided dodecahedron.

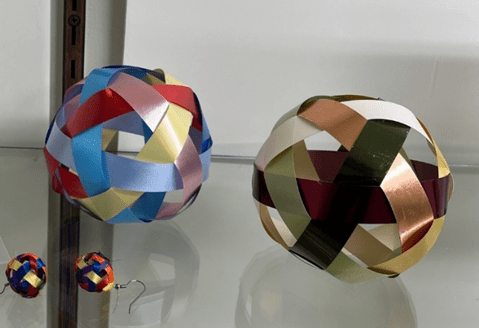

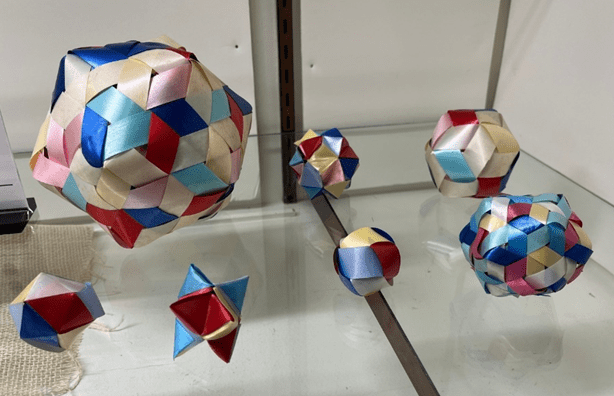

These balls, and many variants, are currently on display in the cases in the hall of the lower level of the Kendal Center. The interest in the balls has been so strong that I may need to offer a class at Kendal in how to make dodecaballs.

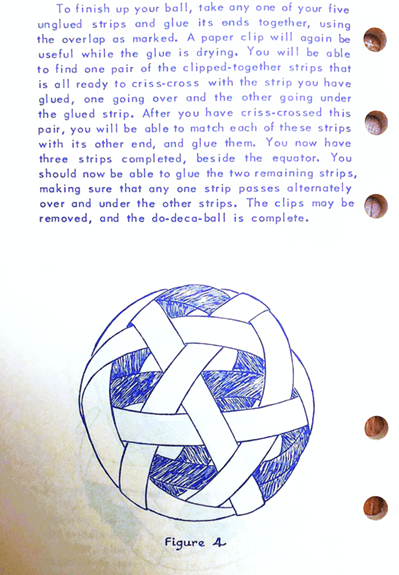

Six ribbons are required are required for a dodecaball, each 16 times as long as it is wide (plus a bit of extra overlap for gluing). The image shown below is a page from my father’s first attempt (circa 1950) to explain a method for making the balls. That method did not turn out to be very successful.

Over the years Dad developed efficient methods for making the balls and taught them to his five kids. We siblings have gone on to teach Dad’s method to others. The method is a bit tricky and easily forgotten, but we haven’t come up with anything better.

Frames for making balls. The difficulty in training others led me to try to develop a type of frame that would make it easy for others to make balls. Here you see various iterations of the frame, from the 1980s onward. For these frames, the idea was that the user would weave the ball on the inside of the frame, then take the frame apart to release the finished ball.

My 3D printer has made it possible to print a type of frame that I could only have imagined previously. You can see the latest ones below. The colorful one is held together by a bolt, which is removed to release the finished ball after weaving. The white one, an earlier version, is held together by small black 0-rings. A couple of Kendal residents have used the latest one successfully, but it’s still not a great solution. I’m working on it.

Icosaball (10 ribbons). During my freshman year of college, I figured out how to make a ball with 10 ribbons, rather than the 6 of the dodecaball. This became the “icosaball”, because it is based on the symmetry of the 20-sided iscosahedron. I taught my sisters Rachel and Jane, and later our daughter Becky, how to make this. We have not been very successful at teaching others how to make icosaballs. Rachel went on to produce many variants of the icosaball.

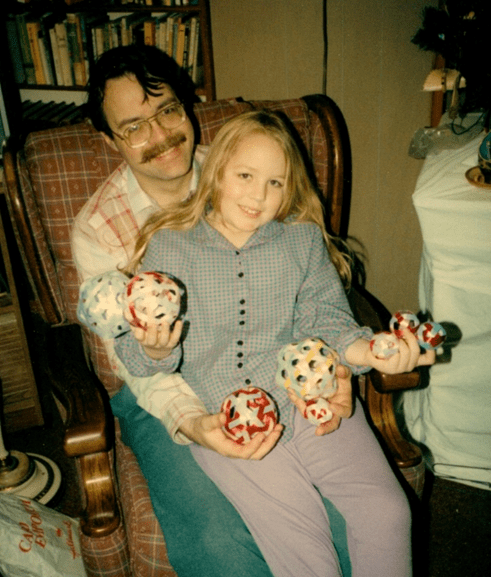

Ball-making session. The photo below shows me and our daughter Becky after a joint ribbon-ball-making session in 1989. Becky, age 8, was already a very proficient ball maker.

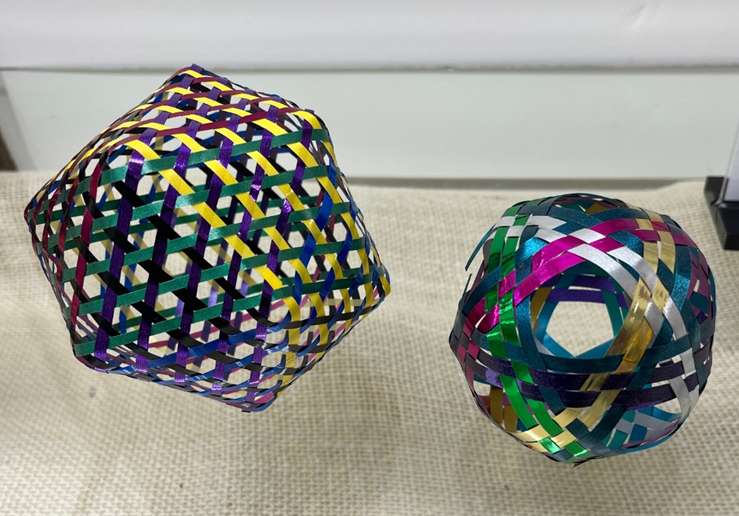

Dodecaball variations & related explorations. My sister Rachel and I have been exploring variants on the basic balls for many years. Rachel did the delicate ones shown below. I did the solid-woven ones below that.

None of the balls shown in this post required any kind of internal support during weaving. The plastic ribbon I use is stiff enough to hold its circular shape when the ends are glued together. Once fully woven, the ribbons take the shape of a sphere without requiring any prodding. Paper strips also work well.

Soft, flexible cloth ribbon is not suitable for this purpose. You can make a ball, but it is likely to collapse from its own weight

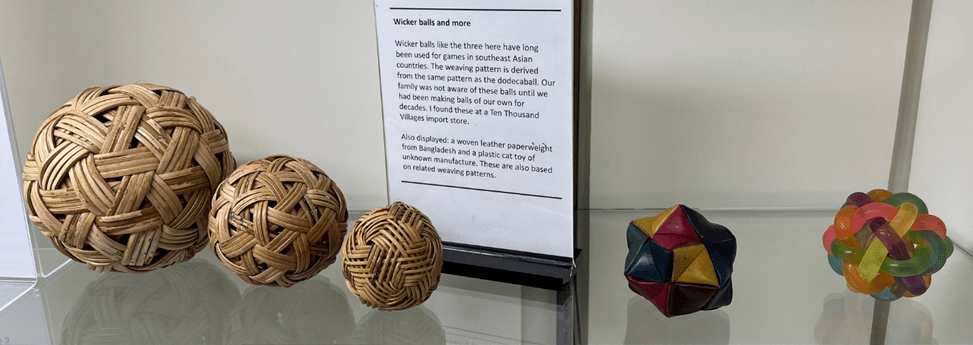

Wicker balls and more. Wicker balls like the three shown here (below left) have long been used for games in southeast Asian countries. The weaving pattern is derived from the same pattern as the dodecaball. Our family was not aware of these balls until we had been making balls of our own for decades. I found these (from Laos and Thailand) at a Ten Thousand Villages import store.

Also shown (below right): a woven leather paperweight from Bangladesh and a plastic cat toy of unknown manufacture. These are also based on related weaving patterns.

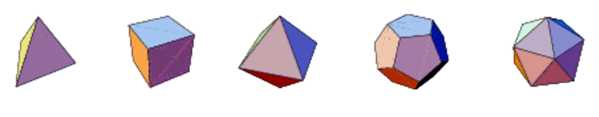

Platonic solids: the basis for the balls. The ball weaving shown in this post is all based on the five so-called “platonic solids”, the only solid forms with identical sides. They were already known to the Greek philosophers, and they are essential parts of geometric knowledge to this day. The five solid forms are shown below. The rightmost two are the dodecahedron and icosahedron, the basis for most of these balls.

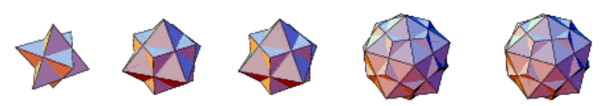

Each of the platonic solids also has a “stellated” form, created by adding a “tent” of equilateral triangles to each face. The stellated forms are the basis for some of the solid-looking ribbon balls (no holes) that I created. Here are the stellated forms.

The balls in the cases on the Lower Level are gorgeous! I’d like to learn how to make one, if my brain and fingers cooperate.

Thanks, Karen Cromley

LikeLike

Yes Please- they’re amazing!

Betsey

LikeLike